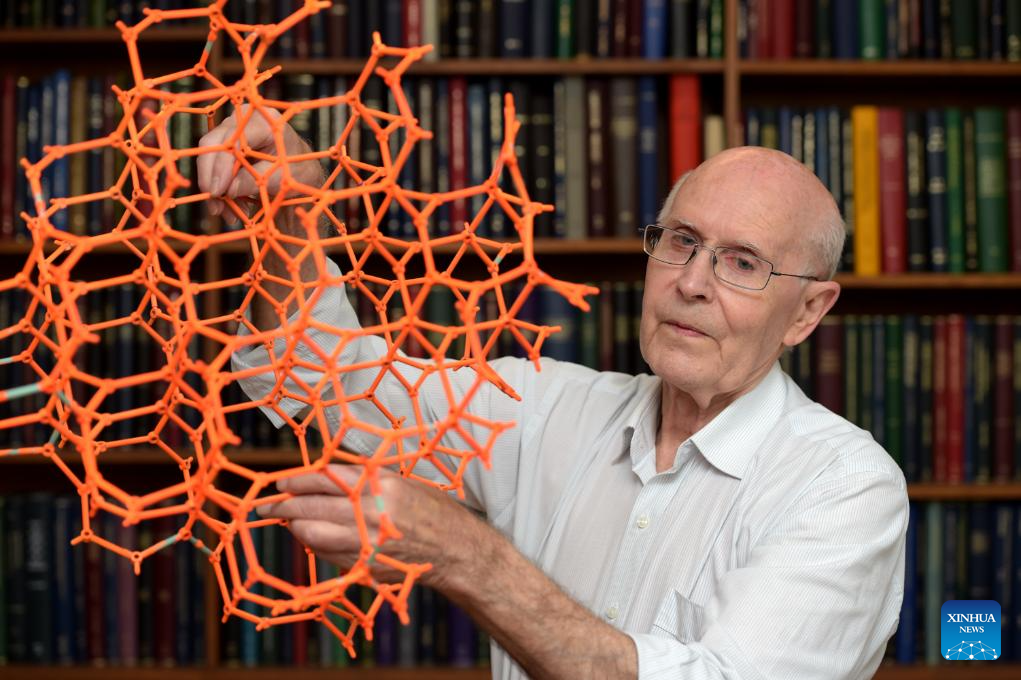

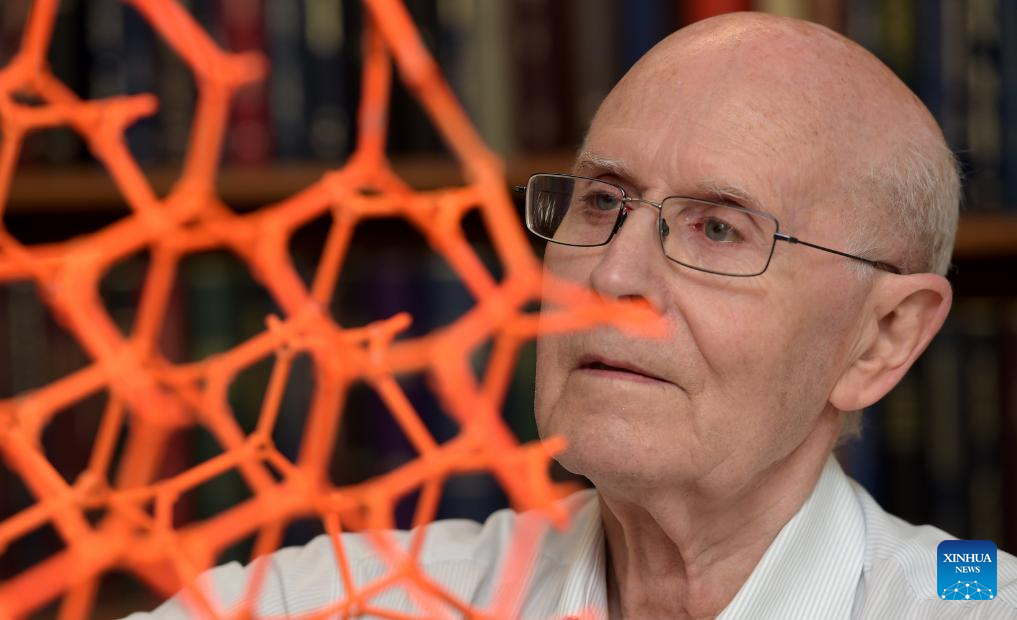

This photo taken on Oct. 9, 2025 shows Professor Richard Robson and the model of metal-organic frameworks in Melbourne, Australia. Richard Robson was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with two other scientists for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). (University of Melbourne/Handout via Xinhua)

STOCKHOLM, Oct. 8 (Xinhua) -- Metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, might sound arcane, but in essence, they are like high-rise apartment blocks for molecules: vast, ordered scaffolds filled with "rooms" where gases and liquids can move freely.

This deceptively simple idea -- building solids with intentional empty space -- has transformed parts of chemistry and materials science, earning Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

WHO ARE THEY AND WHAT DID THEY FIND?

Chemists traditionally focused on making molecules, but this year's laureates turned that logic inside out by building space around molecules.

Beginning in 1989, Robson combined positively charged copper ions with a four-armed organic molecule and obtained a well-ordered crystal laced with cavities -- a diamond-like lattice filled with empty rooms rather than solid matter.

The early frameworks were fragile, but in the 1990s Kitagawa showed that gases could flow in and out of such structures, predicting that some would be flexible, able to "breathe" as guest molecules entered or left.

Kitagawa himself produced a soft, flexible material that expanded when filled with water or methane and returned to its original form when emptied, much like a lung that inhales and exhales gases while remaining structurally stable.

Around the same time, Yaghi developed highly stable frameworks and demonstrated that their size, shape and chemical properties could be tailored by rational design. His work helped transform MOFs from scientific curiosities into a major class of engineered materials.

In 1995, Yaghi published the structure of two two-dimensional frameworks held together by copper or cobalt, which could host guest molecules and withstand temperatures up to 350 degrees Celsius.

In a paper published in Nature, he coined the term "metal-organic framework," now the universal name for these porous, ordered molecular architectures built from metal ions and organic linkers.

A few years later, in 1999, he unveiled MOF-5, a landmark material that combined exceptional stability with vast internal space. Even when empty, MOF-5 could be heated to 300 degrees Celsius without collapsing. Just a few grams of it offered an internal surface area equivalent to a football field, allowing it to absorb far more gas than traditional materials like zeolites.

WHY THE DISCOVERY MATTERS

"Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar Yaghi are awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025 because they created the first MOFs and demonstrated their potential," the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said in a statement.

Their pioneering work has since enabled chemists to design tens of thousands of MOFs with tailored properties and uses. In industry, MOFs can safely store or neutralize hazardous gases used in semiconductor manufacturing or break down toxic compounds. Companies are also testing MOFs to capture carbon dioxide from factories and power plants, a promising tool to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Zou Xiaodong, a member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, told Xinhua that MOFs could be pivotal in addressing climate change.

To reduce emissions, she noted, carbon dioxide must first be separated from other gases so it can be stored -- an energy-intensive step that accounts for a large part of the capture costs.

"With their large surface area and strong adsorption, MOFs could significantly lower those costs," she said.

Zou added that research on MOFs is advancing rapidly worldwide. "As far as I know, there are more than 100 laboratories in China alone conducting related research," she said.

Beyond carbon capture, the Academy noted, MOFs may help tackle other urgent challenges -- from filtering PFAS "forever chemicals" from water and degrading pharmaceutical residues, to harvesting drinking water directly from desert air. ■

This photo taken on Oct. 9, 2025 shows Professor Richard Robson receiving an interview with University of Melbourne media team in Melbourne, Australia. Richard Robson was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with two other scientists for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). (University of Melbourne/Handout via Xinhua)

This photo taken on Oct. 9, 2025 shows Professor Richard Robson and the model of metal-organic frameworks in Melbourne, Australia. Richard Robson was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with two other scientists for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). (University of Melbourne/Handout via Xinhua)

This photo taken on Oct. 9, 2025 shows Professor Richard Robson and the model of metal-organic frameworks in Melbourne, Australia. Richard Robson was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with two other scientists for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). (University of Melbourne/Handout via Xinhua)

This photo taken on Oct. 9, 2025 shows Professor Richard Robson receiving an interview with University of Melbourne media team in Melbourne, Australia. Richard Robson was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with two other scientists for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). (University of Melbourne/Handout via Xinhua)